If you’re new to manufacturing or looking to understand the basics of shaping metal and other materials, you might be asking: What exactly is manual machining, and why is it still relevant today? Simply put, manual machining is the process of using hand-operated or manually controlled machines—like lathes, mills, and drills—to cut, shape, and finish raw materials into precise parts. Unlike automated CNC (Computer Numerical Control) machining, it relies on the operator’s skill, experience, and ability to make real-time adjustments. Even with the rise of automation, manual machining remains critical for small-batch production, prototyping, repairs, and situations where flexibility and quick setup are more important than high-volume output. In this guide, we’ll break down everything you need to know, from core concepts to practical tips, to help you grasp and apply manual machining effectively.

Core Definitions: Understanding Manual Machining Fundamentals

Before diving into techniques, it’s essential to clarify what manual machining entails and how it differs from other methods. At its core, manual machining is about material removal—using cutting tools to remove excess material from a workpiece (the raw material being shaped) until it meets specific dimensions and tolerances (the allowed variation from the exact design).

The key distinction between manual and CNC machining lies in control: In manual machining, the operator adjusts the machine’s movements directly (e.g., turning handwheels to move a cutting tool) based on visual inspection and measurements. In CNC machining, a computer program controls these movements automatically. This doesn’t make manual machining “outdated,” though—its strength lies in adaptability. For example, if a prototype needs a last-minute design tweak, a manual machinist can adjust the process on the spot, whereas a CNC program would require recoding and testing.

Another critical term is machining accuracy. Manual machining typically achieves tolerances of ±0.001 to ±0.005 inches (depending on the machine and operator skill), which is sufficient for many applications like custom brackets, repair parts, or low-volume components. For reference, a human hair is about 0.003 inches thick—so manual machining can produce parts with precision finer than a hair’s width when done correctly.

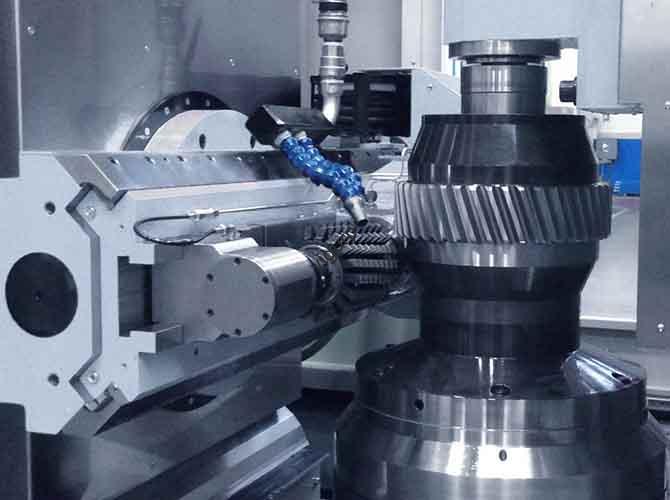

Essential Manual Machining Tools and Their Uses

To perform manual machining, you’ll need a set of core machines and tools. Each serves a unique purpose, and mastering their operation is key to success. Below is a breakdown of the most common equipment, along with real-world use cases to illustrate how they’re applied.

| Machine Type | Primary Function | Key Components | Real-World Example |

| Manual Lathe | Rotates the workpiece while a stationary cutting tool shapes it (ideal for cylindrical parts) | Headstock (holds workpiece), tailstock (supports long workpieces), tool post (holds cutting tool), handwheels (controls tool movement) | A machinist using a lathe to turn a metal rod into a bolt with threaded ends. |

| Manual Milling Machine | Uses a rotating cutting tool to remove material from a stationary workpiece (great for flat surfaces, slots, or complex shapes) | Worktable (holds workpiece), spindle (rotates cutting tool), feed handles (move worktable) | Creating a slot in a aluminum plate for a gear to fit into using a vertical milling machine. |

| Drill Press | Makes precise holes in a workpiece using a rotating drill bit | Base (supports workpiece), column (holds spindle), chuck (secures drill bit) | Drilling holes in a steel bracket for mounting screws in a small furniture manufacturing shop. |

| Grinder | Uses an abrasive wheel to smooth, sharpen, or shape workpieces (critical for finishing) | Abrasive wheel, tool rest (supports workpiece), adjustable guard | Sharpening a dull cutting tool for a lathe or smoothing the rough edge of a metal part after milling. |

In addition to these machines, manual machinists rely on measuring tools to ensure accuracy. Common ones include calipers (for measuring length and thickness), micrometers (for ultra-precise measurements down to 0.0001 inches), and dial indicators (for checking if a workpiece is level or aligned). For example, when machining a shaft on a lathe, a machinist might use a micrometer every few cuts to ensure the diameter stays within the required tolerance.

Step-by-Step Guide to a Basic Manual Machining Project

To make manual machining tangible, let’s walk through a practical project: creating a simple metal spacer (a small cylindrical part used to fill gaps between components). This project uses a manual lathe and covers key steps like setup, cutting, and finishing.

1. Gather Materials and Tools

- Workpiece: A 6-inch long, 1-inch diameter aluminum rod (aluminum is ideal for beginners because it’s softer and easier to cut than steel).

- Machine: Manual lathe.

- Cutting Tool: High-speed steel (HSS) turning tool (suitable for aluminum).

- Measuring Tools: Calipers, micrometer, ruler.

- Safety Gear: Safety glasses, work gloves, ear protection (lathes can be loud).

2. Set Up the Lathe

- Mount the Workpiece: Insert one end of the aluminum rod into the lathe’s headstock chuck and tighten it securely. Use the tailstock to support the other end (this prevents the rod from bending during cutting).

- Align the Cutting Tool: Attach the HSS turning tool to the tool post. Adjust the tool’s height so its cutting edge is level with the center of the workpiece (if it’s too high or low, it will produce a rough cut).

- Set Speed: For aluminum, set the lathe to a speed of 1,500–2,000 RPM (rotations per minute). Harder materials like steel require slower speeds (500–1,000 RPM) to avoid damaging the cutting tool.

3. Perform Rough Cutting

- Start the Lathe: Turn on the machine and let it reach full speed.

- Make the First Cut: Use the handwheels to move the cutting tool toward the workpiece. Apply light pressure to remove a thin layer of aluminum (about 0.010 inches) along the length of the rod. This “rough cut” shapes the workpiece close to the final size but leaves extra material for finishing.

- Measure Often: Stop the lathe every 2–3 cuts and use calipers to check the diameter. For a spacer that needs to be 0.75 inches in diameter, stop rough cutting when the diameter is 0.760 inches (leaving 0.010 inches for finishing).

4. Finish Cutting and Smooth the Surface

- Reduce Speed: Lower the lathe speed to 1,000–1,500 RPM for finishing.

- Make Fine Cuts: Adjust the cutting tool to remove small amounts of material (0.002–0.005 inches per cut) until the diameter reaches exactly 0.75 inches (use a micrometer for precise measurement here).

- Smooth the Surface: Use a “finishing pass”—a slow, light cut along the length of the workpiece—to remove any tool marks. This gives the spacer a smooth, professional look.

5. Remove and Inspect the Workpiece

- Stop the Lathe: Turn off the machine and wait for it to stop completely.

- Remove the Spacer: Loosen the chuck and tailstock, then carefully take out the spacer.

- Check Tolerances: Use a micrometer to confirm the diameter is 0.75 inches ±0.001 inches. If it’s too big, you can make a final fine cut; if it’s too small, you’ll need to start with a new rod (a common mistake for beginners, which is why measuring often is key!).

Common Challenges in Manual Machining and How to Overcome Them

Even experienced machinists face challenges with manual machining—since it relies on human skill, small mistakes can lead to flawed parts. Below are the most common issues and practical solutions, based on industry experience.

1. Inconsistent Tolerances

Problem: The workpiece’s dimensions vary outside the allowed tolerance (e.g., a bolt that’s too thick to fit into a nut). This often happens when the operator rushes cuts or doesn’t measure frequently.

Solution:

- Measure after every 2–3 cuts, not just at the end.

- Use a dial indicator to check if the workpiece is aligned correctly in the lathe or mill (misalignment causes uneven cutting).

- Practice “light cuts”—removing small amounts of material (0.002–0.005 inches) at a time—for better control.

Example: A beginner machinist was making 0.020-inch cuts on a steel rod, leading to a final diameter that was 0.003 inches too small. By switching to 0.005-inch cuts and measuring after each, they achieved the correct tolerance within two more attempts.

2. Tool Wear and Damage

Problem: Cutting tools become dull or break, leading to rough cuts or uneven surfaces. This is often caused by using the wrong tool material (e.g., a low-speed tool on a high-speed cut) or not lubricating the tool-workpiece interface.

Solution:

- Match the tool to the material: Use HSS tools for aluminum and brass (softer materials) and carbide tools for steel and stainless steel (harder materials).

- Use cutting fluid (lubricant) to reduce friction and heat—this extends tool life by up to 50%, according to manufacturing industry data.

- Sharpen tools regularly using a grinder; a dull tool requires more pressure, increasing the risk of breakage.

3. Poor Surface Finish

Problem: The workpiece has visible tool marks, scratches, or roughness, making it unsuitable for applications where appearance or smoothness matters (e.g., a decorative part or a component that needs to slide against another part).

Solution:

- Use a finishing tool with a sharp, polished cutting edge (dull tools leave more marks).

- Reduce the lathe/mill speed for the final pass (slower speeds create smoother cuts).

- After machining, use a grinder or sandpaper (400–600 grit) to polish the surface—this is especially helpful for aluminum parts.

The Role of Manual Machining in Modern Manufacturing

You might wonder: With CNC machining dominating high-volume production, why is manual machining still important? The answer lies in its unique advantages that automation can’t replace—especially for small businesses, startups, and repair shops.

1. Prototyping and Small-Batch Production

CNC machines require time to program (often several hours for complex parts) and are most cost-effective for runs of 100+ parts. Manual machining, by contrast, can be set up in 10–15 minutes, making it ideal for prototyping (where you might only need 1–5 parts) or small batches. For example, a startup developing a new kitchen gadget might use manual machining to create 10 prototype parts, test them, and make design changes quickly—without investing in CNC programming.

2. Repairs and Maintenance

When a machine part breaks (e.g., a gear in a factory conveyor belt), waiting for a CNC shop to program and produce a replacement could take days. A manual machinist can measure the broken part, create a new one on the spot, and get the machine running again in hours. This is critical for industries like agriculture, where downtime during harvest season can cost thousands of dollars per day.

3. Skill Development for Machinists

Manual machining is often called the “foundation of machining” because it teaches operators to understand how cutting tools interact with materials, how to read blueprints, and how to troubleshoot problems. Many CNC machinists start with manual machining experience—this hands-on knowledge helps them write better CNC programs and fix issues when automated machines fail. According to the National Institute for Metalworking Skills (NIMS), 78% of CNC machinists report that manual machining experience improved their ability to operate CNC equipment.

Safety Best Practices for Manual Machining

Safety is non-negotiable in manual machining—machines have moving parts and sharp tools that can cause serious injury if not used correctly. Below are essential safety rules, based on guidelines from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and industry standards.

- Wear Proper PPE (Personal Protective Equipment): Always use safety glasses (to protect against flying chips), work gloves (to prevent cuts from sharp edges), and ear protection (lathes and mills can reach 85+ decibels, which damages hearing over time). Avoid loose clothing or jewelry—these can get caught in moving parts.

- Inspect Machines Before Use: Check that guards are in place (e.g., the lathe chuck guard), tools are secure (no loose cutting bits), and moving parts are lubricated. If a machine makes unusual noises or vibrations, stop using it immediately and report the issue.

- Never Reach Over a Running Machine: Keep your hands and arms clear of moving parts. If you need to adjust the workpiece or tool, turn off the machine first.

- Secure Workpieces Properly: Use chucks, clamps, or vises to hold the workpiece tightly. A loose workpiece can fly off the machine, causing injury or damage.

- Clean Up as You Go: Use a brush (not your hands) to remove metal chips from the machine—chips are sharp and can cause cuts. Keep the work area free of clutter to avoid tripping.

Yigu Technology’s Perspective on Manual Machining

At Yigu Technology, we recognize manual machining as a vital skill that complements automated manufacturing. While we leverage CNC technology for high-volume, precision-critical projects, we still rely on manual machining for prototyping and custom repairs. It allows our team to test design iterations quickly—saving time and resources during product development. We also believe manual machining is essential for training new engineers: it builds a deep understanding of material behavior and tool dynamics that automation alone can’t teach. For small businesses and startups, manual machining remains an accessible, cost-effective way to bring ideas to life—filling a gap that CNC machining can’t cover for low-volume needs.

FAQ About Manual Machining

1. Is manual machining harder to learn than CNC machining?

Manual machining requires more hands-on skill and real-time decision-making (e.g., adjusting tool pressure based on material feedback), so it can take longer to master the basics. CNC machining, by contrast, focuses on programming and computer skills—once you learn to write G-code (the language CNC machines use), operating the machine is more automated. However, manual machining experience makes learning CNC easier, as it teaches you the fundamentals of machining logic.

2. What materials can be used in manual machining?

You can machine almost any solid material, but the most common are metals (aluminum, steel, brass, stainless steel), plastics (PVC, acrylic), and wood. Softer materials like aluminum and plastic are best for beginners, while harder materials like steel require more skill and specialized tools (e.g., carbide cutting bits).

3. How accurate can manual machining be?

With a well-maintained machine and a skilled operator, manual machining can achieve tolerances of ±0.001 inches (25.4 micrometers)—which is precise enough for most non-aerospace or medical applications. For reference, this is about 1/30 the thickness of a human hair. CNC machining can achieve tighter tolerances (±0.0001 inches), but manual machining is more than sufficient for parts like brackets, spacers, and repair components.

4. Is manual machining cost-effective for small businesses?

Yes! Manual machines have lower upfront costs than CNC machines (a basic manual lathe costs \(2,000–\)5,000, while a CNC lathe starts at $10,000+). They also require less setup time, so small businesses can produce small batches or custom parts without investing in expensive programming. For businesses that only need 1–50 parts at a time, manual machining is often cheaper and faster than CNC.

5. What’s the difference between a lathe and a milling machine in manual machining?

A lathe rotates the workpiece while the cutting tool stays stationary—this is ideal for cylindrical parts like bolts, shafts, or spacers. A milling machine keeps the workpiece stationary while the cutting tool rotates—this is better for flat surfaces, slots, holes, or complex shapes like gears. Think of it this way: a lathe “turns” parts, while a mill “cuts” parts into specific shapes.