If you’re a procurement specialist or product engineer in robotics, mastering the metal robot prototype model process is key to turning design ideas into functional, reliable robots. Metal prototypes let you test durability, movement, and structural stability—critical for avoiding costly mistakes in mass production. Below is a practical, detailed breakdown of every stage, with real cases and data to help you make smart decisions.

1. Material Selection: Pick Metals That Fit Robot Needs

Choosing the right metal is the first big step in building a metal robot prototype. Robots need materials that balance strength, weight, and cost—here’s how to choose:

| Metal Type | Key Properties | Ideal Robot Components | Real-World Example | Cost Range (USD/lb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum Alloy | Low density (2.7 g/cm³), easy to machine | Arm joints, lightweight frames | A factory robot maker used 6061 aluminum for arm prototypes—cut weight by 35% vs. steel, improving movement speed. | $2–$5 |

| Stainless Steel | Corrosion-resistant, high strength | Grippers, outdoor robot bodies | A warehouse robot prototype used 316 stainless steel for grippers—no rust after 8 months of handling wet packages. | $3–$8 |

| Brass | Good electrical conductivity | Sensor mounts, small connectors | A service robot team used brass for sensor prototypes—ensured stable signal transmission during tests. | $8–$12 |

| Magnesium Alloy | Ultra-light, high rigidity | Small robot frames (e.g., drones) | A medical robot prototype used magnesium alloy for its body—weighed 20% less than aluminum, ideal for tight spaces. | $10–$15 |

| Zinc Alloy | Low cost, good castability | Decorative covers, simple parts | A toy robot company used zinc alloy for prototype covers—saved 40% on material costs vs. aluminum. | $1.5–$4 |

Tip for procurement: For robots that move often (e.g., factory arms), aluminum alloy is the best mix of cost and performance. For outdoor use, stainless steel is a must.

2. Data Collection: Lay the Groundwork for Accuracy

You can’t build a good prototype without clear data. This stage ensures your prototype matches your design exactly.

2.1 Import 3D/CAD Files

Ask your design team or client for 3D drawings or CAD files—these are the blueprint for your prototype. Without them, you risk misinterpreting sizes or shapes.

Common tools: AutoCAD (for 2D files), SolidWorks (for 3D models), Fusion 360 (great for small teams).

Example: A robot startup once skipped checking CAD files—their prototype’s arm joint was 1mm too small, so it couldn’t move smoothly. Always verify file details first!

2.2 Create Initial Prototypes

Turn 2D/3D files into simple prototypes to test basic fit. Two common methods:

- SLA Laser Rapid Prototyping: Fast (1–2 days) for small, detailed parts (e.g., sensor brackets).

- CNC Machining: Better for larger, sturdier parts (e.g., robot frames).

Case: A logistics robot team used SLA to make gripper prototypes—they realized the grippers were too narrow for boxes, fixing the issue before full machining.

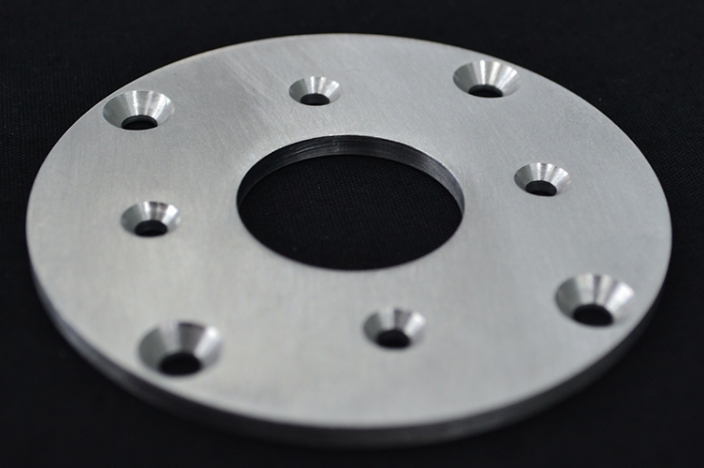

3. CNC Machining: Turn Metal into Robot Parts

CNC machines are the heart of metal robot prototype manufacturing—they make precise parts quickly.

3.1 Programming & Setup

Engineers write code for the CNC machine using your 3D/2D files. This code tells the machine how to cut, drill, and shape the metal.

Key benefits:

- High accuracy (tolerances as tight as ±0.001mm) – critical for robot joints that need smooth movement.

- Consistent results – every part is the same, so assembly is easy.

Example: A factory robot maker used CNC programming for arm prototypes—all 10 parts fit perfectly, no rework needed.

3.2 Multi-Axis Machining

For complex parts (e.g., curved robot bodies or multi-angle joints), use multi-axis CNC machines (3-axis, 5-axis, or more).

- 3-axis machines: Good for simple parts (e.g., flat frames).

- 5-axis machines: Reach hard-to-access areas (e.g., inside arm joints) – cuts production time by 30% vs. 3-axis.

Stat: 5-axis machining reduces prototype errors by 50% compared to traditional methods (per robotics manufacturing data).

4. Manual Processing: Fix Small Flaws

Even CNC parts need a little hands-on work to be perfect.

4.1 Deburring

Use sandpaper, deburring tools, or brushes to smooth sharp edges and knife marks on metal parts. This prevents scratches on other components or workers.

Why it matters: A robot arm prototype once had a sharp edge—during testing, it scratched a conveyor belt. Deburring fixes this easy-to-miss issue.

4.2 Grinding & Polishing

Check your drawings to ensure the surface is smooth enough. For example:

- Robot joints need polished surfaces to move without friction.

- External covers need grinding to look neat.

Example: A service robot team polished their prototype’s body—testers said the smooth surface was easier to clean, a big plus for public spaces.

5. Appearance Treatment: Boost Durability & Looks

Robots need to last and look good—surface treatment does both.

Key Surface Processes for Metal Robot Prototypes

| Process | Purpose | Ideal Robot Components |

|---|---|---|

| Painting | Add color, hide scratches | External bodies, covers |

| Sandblasting | Create a matte, non-slip surface | Grippers, foot pads |

| Oxidation | Prevent rust (for aluminum parts) | Arm joints, frames |

| Laser Engraving | Add logos or labels (e.g., “Power”) | Control panels |

| Silk Screen Printing | Add text (e.g., “Caution”) | Safety covers, buttons |

Case: An outdoor robot company used oxidation on aluminum arm prototypes—after 6 months in rain and snow, there was no rust, and the arms moved like new.

6. Assembly & Testing: Make Sure the Robot Works

Put all parts together, then test if the prototype functions as planned.

6.1 Test Assembly

First, assemble the prototype to check:

- Do parts fit? (e.g., Does the arm attach to the body correctly?)

- Is the structure stable? (e.g., Can the robot hold 5kg without tipping?)

Example: A medical robot team tested assembly and found the sensor mount was misaligned—they adjusted it, avoiding a failure in functional tests.

6.2 Functional Testing

Test how the prototype performs in real situations:

- Structural stability: Shake the robot to see if parts loosen.

- Mechanical properties: Check if joints move smoothly (e.g., Can the arm lift 3kg 100 times?).

- Simulated use: Run the robot in a test environment (e.g., a factory robot moving boxes).

Case: A warehouse robot prototype failed a simulated use test—it couldn’t grip wet boxes. The team added a rubber layer to the grippers, fixing the problem.

7. Packaging & Shipping: Protect Your Prototype

Don’t ruin your hard work with bad packaging.

- Safe packaging: Use foam, bubble wrap, or custom boxes to prevent damage. For example, robot arms need rigid packaging to avoid bending.

- On-time delivery: Work with reliable logistics to meet deadlines. Most robotics teams need prototypes in 2–3 weeks to stay on schedule.

Tip: Add a packing list—this helps clients check if all parts (e.g., screws, sensors) arrive.

Yigu Technology’s Perspective

At Yigu Technology, we know the metal robot prototype model process thrives on precision and practicality. Many teams overcomplicate it—like using 5-axis machining for simple frames when 3-axis works. We work with clients to pick materials (e.g., aluminum for moving parts, stainless steel for outdoors) and processes that fit their goals. Our manual processing and testing teams focus on real use: we don’t just build prototypes—we build robots that work when it matters. This balance saves time, cuts costs, and gives clients confidence in their final product.

FAQ

- Q: How long does it take to make a metal robot prototype?

A: It depends on complexity. Small parts (e.g., sensor brackets) take 1–2 weeks. A full robot prototype (e.g., a factory arm) takes 3–4 weeks, including design and testing. - Q: Which material is best for a metal robot prototype on a tight budget?

A: Zinc alloy or aluminum alloy (6061 grade). Zinc is cheap for simple parts, while 6061 aluminum is affordable and works for most moving components. - Q: Do I need to test assembly before functional testing?

A: Yes! Assembly testing catches fit issues (e.g., misaligned parts) that functional tests might miss. Skipping it can waste time—fixing assembly problems later takes 2x longer.